|

|

Introduction

The DVI Pre-Post is available on www.online-testing.com.

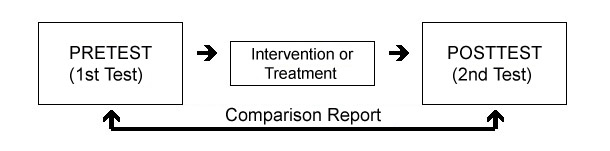

The DVI Pre-Post evolved from the Domestic Violence Inventory (DVI). The DVI Pre-Post has 147 items and takes 25 to 30 minutes to complete. DVI Pre-Post scale scores reflect the here-and-now. Scale score comparisons (pre-test/post-test) can improve, stay the same, or decline. The DVI Pre-Post does not interpret, judge, or state opinions about treatment program effectiveness, or treatment outcome. It simply reports positive or negative change in DVI Pre-Post scale scores. Indeed, the intent is to objectively report pre-test/post-test change. The DVI Pre-Post is an objective and standardized treatment effectiveness, or outcome test. It provides evidence-based scales and objectively based outcome measures. The DVI Pre-Post personifies evidence-based assessments.

Did the domestic violence offender get better, stay the same, or get worse? Historically, this straightforward question has been difficult to answer accurately or objectively. Assessors, treatment staff, and program administrators have been searching for a meaningful, standardized and objective outcome, or treatment effectiveness measure. The DVI Pre-Post was developed to meet this need.

It would be a mistake to assume domestic violence perpetrators have been rehabilitated, positively changed, or made well, simply because they have completed assigned or mandated treatment (Broome, Flynn, Knight and Simpson, 2007). Some domestic violence offenders do not benefit from treatment (Mechanic, Weaver, Rosnick, 2000).

To review an example "pre-test report" or "comparison report," click on the navigational links at the top of the page.

DVI Pre-Post

The Domestic Violence Inventory DVI Pre-Post or DVI Pre-Post is a self-report test designed to measure domestic violence counseling and treatment effectiveness, or change. The same test is administered before and after treatment (counseling, domestic violence treatment or psychotherapy). Upon post-test (2nd test), it automatically compares pre-test and post-test results. The DVI Pre-Post contains six (6) scales (measures): 1. Truthfulness Scale, 2. Violence (Lethality) Scale, 3. Control Scale, 4. Alcohol Scale, 5. Drug Scale, and 6. Stress Management Scale. The DVI Pre-Post objectively compares pre-test and analogous post-test scale scores, and reports "change." If you want to know the effects of domestic violence treatment, you should consider the DVI Pre-Post.

Reports

In brief, there are two DVI Pre-Post reports: The pre-test (1st test administration) report and the post-test (2nd test administration) comparison report. It is the pre-test/post-test (comparison) report that most people are interested in. Post-test scale scores are automatically compared to pretest scale scores and within 3 minutes of test data entry, pre-test/post-test comparisons are made, and the "comparison report" is printed on site. Comparison reports summarize a lot of information in an easily understood format. To review a comparison report, click on this Comparison Report link.

DVI Pre-Post Scale Descriptions

Truthfulness Scale: A common weakness of domestic violence recidivism research, is that most assessment instruments, or tests do not control for offender truthfulness (Bishop, 2009). Domestic violence perpetrators often deny violent behavior and portray themselves as victims (Kimberg, 2008).

The DVI Pre-Post uses a Truthfulness Scale to determine offender truthfulness while they are being tested. The DVI Pre-Post uses a procedure similar to the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) scale, the DVI Pre-Post "Truth-Corrects" its scale scores. The DVI Pre-Post Truthfulness Scale determines if the offender's answers are truthful.

Socially desirable answers can have a significant impact on assessment results (Blanchette, Robinson, Alksnis and Serin, 1997): Domestic violence offender denial and problem minimization have been shown to exacerbate lack of treatment progress (Murphy & Baxter, 1997), increase the probability of treatment dropouts (Daly & Pelowski, 2000), as well as recidivism (Kropp, Hart, Webster & Eaves, 1995); Grann & Wedin, 2002). Reluctance or refusal to take responsibility for one's behavior can indicate a lack of motivation and desire to change (Scott & Wolfe, 2003).

Violence (Lethality) Scale: The DVI Pre-Post Violence (Lethality) Scale measures offenders' domestic violence potential, predisposition, and proneness (Davignon, 2006). Elevated (70th percentile and higher) Violence Scales scores identify offenders who have a problem with violent behavior. A severe (90th to 100th percentile) Violence Scale score represents severe violence. Research shows that the probability of re-occurring, domestic violence increases, when the offender is generically violent (Gilchrest & Beech, 2006).

A history of violent behavior is a predictor of re-abuse (Harrel and Smith, 1996; Quigley and Leonard, 1996) and is the most commonly examined risk factor in the legal system (Roehl, Guertin 1998). Other researchers recognize prior violence as a predictive factor, but also include other factors (criminogenic needs) like substance abuse, control, and mental health disorders, in their violence-predicting models (Hilton, Harris, Rice, Houghton & Eke, 2008).

The DVI Pre-Post Violence Scale is the point of convergence, of all other DVI Pre-Post scales, e.g. Truthfulness Scale, Alcohol Scale, Drug Scale, Control Scale, and the Stress Management Scale. An elevated (70th percentile and higher) Violence Scale score, with other co-occurring scale scores, would indicate other scales are exacerbating violence, and/or vice versa. The DVI Pre-Post pre-test score determines pre-treatment violence severity. The post-test violence scale score establishes violence severity at treatment completion, and as warranted, identifies treatment success, or the need for continued or altered violence treatment.

Alcohol and Drug Scales: Research literature presents strong support for the association between substance (alcohol and other drugs) abuse and domestic violence (Leonard & Roberts, 1996; Stuart, Moore, Kahler & Ramsey, 2003). The DVI Pre-Post Alcohol Scale and Drug Scale are independent of one another, which enables specific problem identification and measurement. This scale independence facilitates matching of problem (alcohol and/or other drugs) severity, with treatment intensity.

Research indicates that prior drug-related arrests are associated with unsuccessful domestic violence treatment. Roberts (1998) found that 70 percent of domestic violence offenders were under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs, at the time of their assault. When substance abuse is problematic, substance abuse treatment is an important component of domestic violence offender therapy (Stuart, 2005). Indeed, the results of the Jones & Gondolf (2001) study indicated the problem, of violence recidivism following substance abuse treatment, decreased.

To enhance accuracy and specificity, the DVI-Pre-Post has an independent Alcohol and Drug Scale. Separate Alcohol Scales and Drug Scales make specific Alcohol and/or Drug Scale problem identification, problem measurement, and problem severity-treatment intensity matching possible.

Control Scale: Another important component of domestic violence is control. Attaining power and control over their victim, is often the primary goal of domestic violence perpetrators (Hines & Douglas, 2010). "Domestic violence may occur when the perpetrator feels that they are losing control and attempts to recapture it." (Gondolf, 1985; Umberson, Anderson, Glick, and Shapiro, 1998). There is also some research support for the finding that female offenders also resort to domestic violence, as a means of maintaining control (Graham-Kevan, and Archer, 2008).

The DVI Pre-Post Control Scale measures the severity of offenders' need to control. In domestic violence jargon, control usually refers to the process of regulating or restraining others. Controlling behaviors include intimidation, threatening, disparaging, hitting and battering. The Control Scale measures the severity of the offenders need to control so that problem severity can be matched with treatment intensity.

Elevated (70th percentile and higher) DVI Pre-Post scales are problematic. Co-occurring, scale score elevations represent co-occurring problems, or disorders. The higher the scale score is, the more severe the problem. Elevated (70th percentile and higher) and severely elevated (90th percentile and higher), co-occurring scales (e.g., Violence Scale, Alcohol Scale, Drugs Scale, Stress Management Scale), invariably exacerbate domestic violence perpetrators' need for control.

Stress Management Scale: Dr. Hans Selye, an authority on stress, noted "Stress not only affects your body, but your emotions, mind and spirit (Litvak, 1979). Everyone must deal with stress, anxiety and frustration."

High rates of domestic violence have been shown to occur among people experiencing stressful life events and chronic stress (Frye and Karney, 2006). Other research suggests that the frequency and perceived impact of stress, contributes to domestic violence (Cano and Vivian, 2001; Langer, Lawrence and Barry, 2008). Individuals who do not possess effective stress management skills, are at increased risk to a variety of health and adjustment problems, including violence (Umberson, Williams, and Anderson, 2002) and substance (alcohol and other drugs) abuse (Cooper, Russell, Skinner, Frone and Mudar, 1992).

The Stress Management Scale includes stressful events, positive coping skills, and stress handling strategies. Consequently, the Stress Management Scale assesses both stressful events and positive coping skills, which, when combined, result in the Stress Management Scale score.

Validity: DVI Pre-Post research extends over two decades. Using several validation methods, validity studies have been conducted on thousands of domestic violence offenders. Early studies used criterion measures. DVI Pre-Post scales were validated with other tests, e.g., Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) L, F and K scales, polygraph examinations, Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale, Treatment Intervention Inventory, Domestic Violence Inventory, SAQ- Adult Probation III, etc. Much of this research is summarized in the document "DVI Pre-Post: Inventory of Scientific Findings" (Davignon, 2004), and recently updated by Rahnuma Khandaker, 2011.

Since the DVI Pre-Post was validated with other tests, the present analysis examines differences between First Offenders (2,025, 74.8%) who reported no more than one domestic violence arrest, and Multiple Offenders (684, 25.2%) who reported two or more domestic violence arrests. A total of 2,792 domestic violence perpetrators were administered the DVI Pre-Post. There were 83 offenders who did not report arrest information; consequently, they were not included in the First, versus Multiple, Offender analysis. In sum, 2,792 domestic violence offenders were administered the DVI Pre-Post as part of treatment program, admission procedures, from January 2009 through May 2011.

It was hypothesized that Multiple Offenders would attain significantly higher (more severe) DVI Pre-Post scale scores, than First Offenders. Pretest scale scores were examined in this analysis. T-test values are presented in Table 1.

|

DVI Pre-Post Scale Scores. N = 2,792, 2011 |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

T-Value |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

All T-Test values except for the Truthfulness Scale were significant at the p < .001 level of significance.

As shown in Table 1, with the exception of the Truthfulness scale, Multiple Offenders mean pre-test scale scores are significantly higher than First Offenders' average scores. The non-significant difference, between First Offenders and Multiple Offenders Truthfulness Scale scores, indicates that client truthfulness (or denial) remains constant throughout the pre-test (intake)/ post-test (treatment completion) interval. Truthfulness Scale findings will be explored further, in future research.

The Violence Scale T-Test, between First and Multiple Offenders, is highly significant (t=-20.39). The finding that the Violence Scale was so effective, in discriminating between First and Multiple Offenders, is important in treatment intake screening, and treatment plans development. In addition, the Alcohol Scale (t=-27.47) and Drug Scale (t= -16.40) differences, between First and Multiple Offenders, mean scores were also significantly large.

Reliability: Cronbach�s Alpha is a widely-accepted measure of tests' reliability (Cortina, 1993). Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients for the six (6) DVI Pre-Post scales are presented in Table 2.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cronbach alphas of .75 and higher are professionally recognized as reliable (Nunnaly, 1978) and, according to Roberts and Rock (2002), are appropriate for use with risk assessment measurements. |

DVI Pre-Post scale reliability coefficients are consistently robust (at or above .88). The professionally accepted standard for reliability is .75 and higher. All DVI Pre-Post scales exceed this standard. DVI Pre-Post reliability coefficients, obtained in 2011, are most representative. These coefficients are: Truthfulness Scale (.90, p<.001), Alcohol Scale (.92, p<.001), Drug Scale (.88, p< .001), Control Scale (.88, p<.001), Violence Scale (.89, p<.001), and Stress Management Scale (.92, p<.001). These results strongly support the internal consistency (reliability) of DVI Pre-Post scales.

Accuracy: DVI Pre-Post accuracy can be approximated by determining how close actual (or attained) scores come to predicted scale scores. DVI Pre-Post risk ranges are the same as those used in the Domestic Violence Inventory (DVI), and many other risk prediction tests used, in DVI Pre-Post validation (e.g., Drivers Risk Inventory-II, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), SAQ-Adult Probation III, Defendant Questionnaire, Treatment Intervention Inventory, etc.).

These risk range, classification categories are low risk (zero to 39th percentile, 39 percent), medium risk (40 to 69th percentile, 30 percent), problem risk (70 to 89th percentile, 20 percent), and severe problem (90 to 100th percentile, 11 percent). In other words, with a large sample of domestic violence offenders tested with the DVI Pre-Post, it is predicted that 39 percent will score in the low risk range, 30 percent will score in the medium range, 20 percent will score in the problem range, and 11 percent will score in the severe problem range.

This classification system has proven to be fair and accurate. The problem threshold is the 70th percentile and higher, whereas, the severe problem threshold is the 90th percentile and higher. Table 3 shows how attained (or actual), scale scores compare to predicted scale scores.

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

(39.0%) |

(30.0%) |

(20.0%) |

(11.0%) |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| The Truthfulness Scale correction applies to problem range scale scores. Tests with incomplete information and invalid tests (N = 257) were deleted. |

To review Risk Range Classification (Table 3) or DVI Pre-Post scale accuracy, let us begin in the upper left corner with the term Scale, which is above the six (6) DVI Pre-Post scales. Starting with the Control Scale and moving to the right, the next column is labeled Low for low risk scale classification. The bold (39.0%) in parentheses, represents the percentage of clients predicted to score in the low risk range. Then, going down three rows to the Control Scale, the 42.7 represents the percentage of offenders that scored in the low risk, Control Scale category. To the right of 42.7 is a bold 3.7, which represents the difference between predicted and actual attained scale scores. The predicted percentile is 39.0%, whereas, the attained percentage was 42.7, which means the attained or actual percentage, is 3.7 percent higher than predicted. As you continue moving to the right, a similar procedure is applied to the Medium risk category (1.4% difference), to the Problem risk category (0.6% difference), and Severe problem risk category (1.7% difference). This is accurate assessment. Out of 24 possible (6X4) comparisons, the largest, predicted-attained difference is 3.7 percent.

Summary: This document serves as an introduction to the DVI Pre-Post, a domestic violence offender treatment outcome, or effectiveness test. The DVI Pre-Post is administered twice: Once at treatment intake (pre-test) and, again, at treatment completion (post-test). Pre-test scores serve as a baseline for post-test comparison. DVI Pre-Post baseline methodology is objectively oriented. Pre-test/Post-test differences are not interpreted, judged, or discussed in terms of opinions about treatment effectiveness, or the lack of positive outcome. The DVI Pre-Post comparison report, simply refers to positive or negative change. The intent is to objectively report pre-test/post-test change.

The DVI Pre-Post consists of 147 true-false and multiple choice items. Administration time is 25 to 30 minutes. All DVI Pre-Post tests are computer scored, using diskettes or flash drives (www.bdsltd.com), or over the internet (www.Online-Testing.com). This website www.dvi-pre-post.com serves as the reference website for the DVI Pre-Post.

The research study referenced, herein, involved 2,792 domestic violence perpetrators. Of these domestic violence offenders, 2,343 were male and 449 were female. Gender difference, DVI pre-test (1st test) and post-test (2nd test) correlations were analyzed. In addition, DVI Pre-Post validity, reliability, and accuracy were reviewed and reported. Strong support was noted and reported for DVI Pre-Post validity (First versus Multiple Offenders), reliability (Cronbach Alpha coefficients), and accuracy (predicted versus attained or achieved) scale scores.

The DVI Pre-Post is a reliable, valid, and accurate domestic violence offender treatment outcome (or effectiveness) assessment instrument, or test.

Blanchette, K. Robinson, D., Alksnis, C., Serin, R. (1997). Assessing Treatment Outcome Among Family Violence Offenders: Reliability and Validity of a Domestic Violence Treatment Assessment Battery. Correction

Broome, K. M., Flynn, P. M., Knight, D. K., Simpson, D. D. (2007). Program Structure, Staff Perceptions and Client Engagement in Treatment. J Subst Abuse Treatment 2007, 33 (2),

Cano, A. & Vivian, D. (2001). Life stressors and husband-to-wife violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6, 459-480.

Cooper, M. L., Russell, M., Skinner, J. B., Frone, M. R., & Mudar, P. (1992). Stress and alcohol use: Moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 139-152.

Cortina, J.M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 98-104.

Daly, J. & Pelowski, S. (2000). Predictors of dropout among men who batter: A review of studies with implications for research and practice. Violence and Victims, 15, 137-160. [Abstract]. Retrieved May 10, 2011 from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=PMID%3A 11108498

Davignon, D. (2004). Domestic Violence Inventory Pre-Post (DVI PRE-POST): An Inventory of Scientific Findings. Unpublished manuscript. (2004). Retrieved May 7, 2009 from http://www.riskandneeds.com/TestsA_DVI PRE-POST.asp

Frye, N.E. & Karney, B.R. (2006). The context of aggressive behavior in marriage: A longitudinal study of newlyweds. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 12-20.

Graham-Kevan, N. & Archer, J. (2008). DOes controlling behavior predict physical aggression and violence to partners? Journal of Family Violence, 23, 539-548.

Grann, M. & Wedin, I. (2002). Risk factors for recidivism among spousal assault and spousal homicide offenders. Psychology, Crime, and Law, 8, 5-23.

Gondolf, E.W. (1985). Men who batter: An integrated approach for stopping wife abuse. Holmes Beach, FL: Learning Publications.

Harrell, A. & Smith, B.A. (1996). Effects of restraining orders on domestic violence victims. In E.S. Buzawa & C.G. Buzawa (Eds.), Do arrests and restraining orders work? (pp. 214-242). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hilton, N.Z., Harris, G.T., Rice, M.E., Houghton, R.E., & Eke, M.E. (2008). An indepth actuarial assessment for wife assault recidivism: The Domestic Violence Risk Appraisal Guide. Law and Human Behavior, 32, 150-163.

Hines, D.A & Douglas, E. M. Intimate Terrorism by Women Towards Men: Does it Exist? J Aggress Confl Peace Res, July 2010, 2 (3) :36-56.

Jones, A.S. & Gondolf, E.W. (2001). Time-varying risk factors for reassault among batterer program participants. Journal of Family Violence, 16, 345-359.

Kimberg, L. S. (2008). Addressing Intimate Partner Violence with Male Patients: Review and Introduction of Pilot Guidelines.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2596504/ Online publication accessed on May 25, 2011.

Kropp, P.R., Hart, S.D., Webster, C.D., & Eaves, D. (1995). Manual for the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment Guide (2nd ed.). Vancouver, Canada: B.C. Institute on Family Violence.

Langer, A., Lawrence, E., & Barry, R.A. (2008). Using a vulnerability-stress-adaptation framework to predict physical aggression trajectories in newlywed marriage. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 76, 756-768.

Litvak, S. (1979). Unstress Yourself: Strategies for Effective Stress Control. Mainstream Publications.

Leonard, K.E. & Roberts, L.J. (1996). Alcohol in the early years of marriage. Alcohol Health and Research World, 20, 192-196.

Murphy & Baxter, 1997. Motivating batterers to change in the treatment context. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12, 607-619.

Quigley, B.M. & Leonard, K.E. (1996). Desistance of husband aggression in the early years of marriage. Violence and Victims, 11, 355-370.

Roberts, A. (1988). Substance abuse among men who batter their mates: The dangerous mix. Substance Abuse Treatment, 5, 83-87.

Roberts, A.R. & Rock, M. (2002). An overview of forensic social work and risk assessments with the dually diagnosed. In A.R. Rogers & G.J. Greene (Eds.), Social Workers� Desk Reference (pp. 661-668). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roehl, J. & Guertin, K. (1998). Current use of dangerousness assessments in sentencing domestic violence offenders: Final report. State Justice Institute.

Scott, K.L. & Wolfe, D.A. (2003). Readiness to change as a predictor of outcome in batterer treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 879-889.

Stuart, G.L. (2005). Improving violence intervention outcomes by integrating alcohol treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 388-393.

Stuart, G.L., Moore, T.M., Kahler, C.W., & Ramsey, S.E. (2003). Substance abuse and relationship violence among men court-referred to batterer intervention programs. Substance Abuse, 24, 107-122.

Umberson, D., Anderson, K., Glick, J., & Shapiro, A. (1998). Domestic violence, personal control, and gender. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 442-452.

Umberson, D. Williams, K., & Anderson, K. (2002). Violent behavior: A measure of emotional upset? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 189-206.